Bucharest, Romania’s capital, is a lively and eclectic city with a fascinating yet troubled history. A short walking tour will quickly reveal the many architectural styles the city’s has, including its scars. The stark contrasts may even put off some travelers, which is why the city is considered off-the-beaten-path.

But those who want to look beyond the surface will be surprised because Bucharest, though not as polished and clean as other Western capitals, is much closer to what real life is like. In this article, I will tell you how to explore this city, understand its complicated past, and see its hidden beauty.

Bucharest’s historical eras at a glance

Much of the city center is modern and garish, but you can also find splendid 17th-18th-century Orthodox churches and graceful Art Nouveau villas tucked away in quiet neighborhoods. At first sight, it might seem like a chaotic jumble of traffic-choked streets, ugly concrete apartment blocks, and grandiose but unfinished communist developments.

Founded by the princes of Wallachia (one of Romania’s three main historical regions) in the 14th century, it was the region’s capital until the end of the 17th century. It ranked high among Southeastern Europe’s urban centers thanks to its position on the trade route between East and West, Vienna and Constantinople.

However, the city’s most impressive transformations occurred between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. That’s when the French influence completely changed the hectic and rural-medieval architecture of the city. That’s when Bucharest became known as “Little Paris” or the “Paris of the East.”

Unfortunately, this high-quality architecture didn’t last long, and the city lost much of its charm during the communist regime. After WWII, former dictator Ceaușescu demolished many historic centers and heritage monuments throughout Romania, especially in Bucharest.

He imposed his megalomaniac vision and rebuilt large neighborhoods into new centers with a questionable architectural style. Bucharest and other cities slowly started integrating the architectural “scars” left by the former regime only after the revolution against communism in ‘89. New modern buildings were constructed, and the existing heritage was rehabilitated.

In the following sections, we’ll dive deeper into each of these three historical phases, with examples of attractions, places to go, or representative neighborhoods for each. I’ll also share some non-touristy stories most travelers miss, although the best way to experience them will be to visit Bucharest and see for yourself.

Cotroceni

Bucharest’s “Little Paris” years

After Romania gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878, Bucharest underwent its first major transformation. Romanian elites educated in France brought back knowledge and cultural and social norms they were eager to implement at home. This French influence occurred especially in architecture and urban planning, as well as in politics and economics.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Romanian aristocracy was among Europe’s richest and most extravagant. Unfortunately, this lifestyle depended on the exploitation of the poor. In Bucharest, the two extremes of the social scene co-existed: beggars waiting outside the best restaurants and appalling slums within a few steps of the elegant boulevards.

In a short timeframe (30-50 years), the city developed with speed and diversity that it hadn’t for centuries. The economic boom, and flourishing of society and its upper class led to the construction of several landmarks and imposing villas.

Large neo-classical buildings sprang up. Fashionable parks were laid out and landscaped on Parisian models. New boulevards were driven through the existing medieval street pattern, following Haussmann’s Parisian style. That’s how Bucharest earned the nickname “Paris of the East” or “Little Paris.”

Several significant landmarks from this Golden Era still stand today. The elegant Victory Boulevard (Calea Victoriei) stands on the site of the medieval wood-paved road called Podul Mogoșoaiei (meaning “the bridge to Mogoșoaia” – a residential complex on the outskirts of the city).

Boyars first built their residences along it, and this encouraged Bucharest’s most prestigious shops to open along the avenue. Later on, the street was repaved (not with wood anymore). It took its present name in 1918, celebrating the victory of the unification of the three historical regions in Romania. Strolling along the avenue was “a thing” of the aristocratic class. Victory Boulevard was where you could see and meet everybody from the high class.

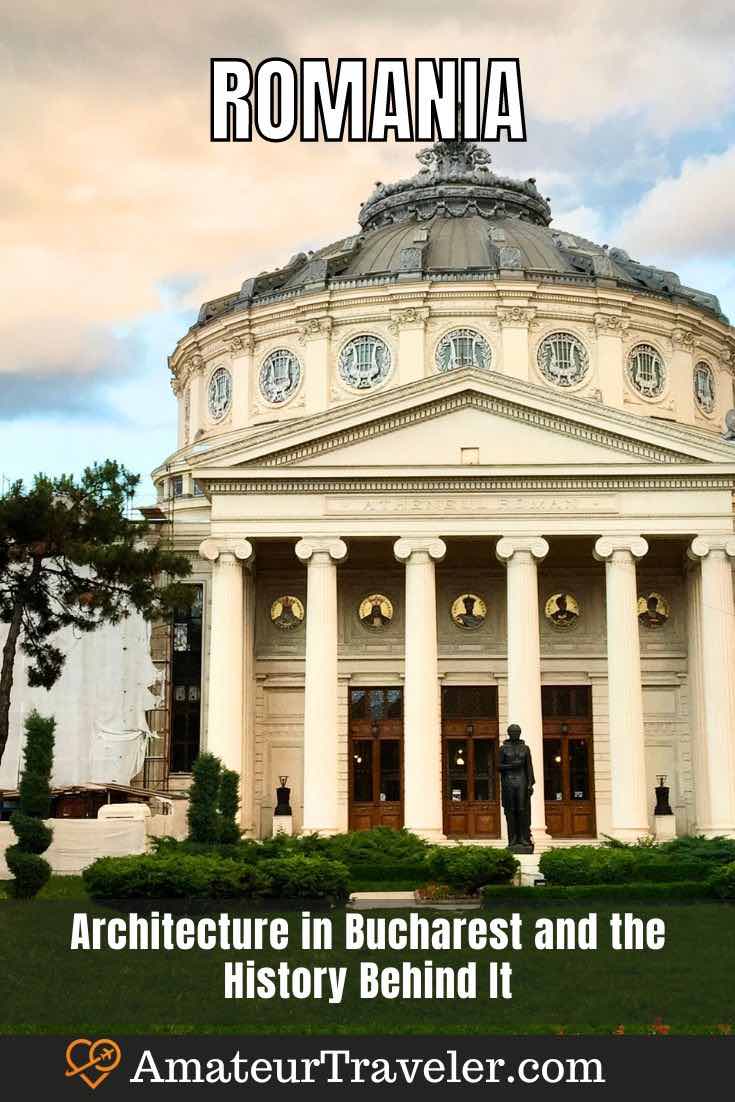

Romanian Athenaeum (1888)

Calea Victoriei has been Bucharest’s most fashionable street ever since. It features eclectic villas of boyar families, historic passageways, fancy coffee shops, and significant interwar architecture. Tourist landmarks here are:

- Telephone Palace was the metropolis’s first “skyscraper,” built in an American-style Art Deco in the interwar period.

- Cantacuzino Palace is a historical palace built in French Beaux-Arts and Rococo Revival styles, housing a museum dedicated to the national composer George Enescu.

- the Romanian Athenaeum is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Here, you can experience the serenity of classical music harmonizing with classical architecture.

A few representative neighborhoods for this period are:

- Cotroceni is an elegant neighborhood with classical Art-Nouveau fenced villas, manicured gardens, and tree-lined streets. Here, you also find Cotroceni Palace – the official residence of the Romanian president.

- Kisselef Boulevard is a long avenue lined with lime trees, modeled on the Parisian urban planning, though named after the Russian general Kiseleff. The avenue is home to some of Bucharest’s finest villas of the Francophilia that swept Romanians’ educated classes during the 19th century.

- The major landmark on one edge of the avenue is the Triumphal Arch. Based on Paris’ namesake monument, the 27-meter arch was built in 1935 to commemorate the reunification of Romania in 1918.

- Aviatorilor Boulevard is a broad, long avenue linking the Triumphal Arch with Victory Square and Street. It features embassies, verdant gardens, and inspiring museums in century-old villas.

As a notable experience from this city era, Capșa Coffee and Pastry Shop on Victory Boulevard (near the city’s kilometer zero) is a traditional coffee shop. It serves delicious pastries and cakes in a historic setting in the heart of Bucharest. Nearby, go to Cișmigiu Garden, one of the city’s Parisian-inspired parks.

Parliament Palace

3. The Communist era

Bombing during WWII coupled with the 1940s earthquake destroyed much of Bucharest’s beauty. When the communist regime came to power in 1947, the well-off aristocrats were stripped of their properties. Since the large majority of the population had almost nothing and struggled to survive and satisfy their basic needs, especially food, the regime promised to reduce the extremes between the poor and the rich.

In 1971, Nicolae Ceaușescu visited North Korea and admired the grandiose avenue in Pyongyang.

A big earthquake in 1977 flattened countless buildings. That was the moment (and excuse) for former dictator Ceaușescu to start a massive city redevelopment project. Inspired by what he saw in North Korea, he set out to remodel Bucharest as the first socialist capital for his ideological socialist man.

The historic city’s architecture, with its cosmopolitan air from the 19th century, was notoriously scarred by Ceaușescu’s project. To implement his grand vision, he massively transformed the city. He ordered the demolition of an entire historical neighborhood that had approx. 9,000 largely undamaged 19th-century houses. Its 40,000 inhabitants were relocated to new developments on the city’s outskirts.

Many old churches were set to be demolished too – since religion was incompatible with the communist regime, yet some were saved by literally moving them or hiding them away behind huge concrete apartment blocks.

The transformation culminated in the early ‘80s when a huge construction project known as the Civic Center began. Made up of the massive Palace of Parliament and Union Boulevard (Bulevardul Unirii) leading up to it, this was meant to demonstrate the communist state’s authority and the megalomania that took over Ceaușescu himself.

The grandiose Palace of the Parliament – also called the House of the People, is a crucial attraction in the Civic Center. It’s the second-largest building in the world after the Pentagon and the most expensive administrative building. It has twelve stories and four underground levels, including a nuclear bunker, 1100 rooms, and a 100-meter-long corridor.

The huge construction cost contributed to the regime’s fall in the 1989 revolution. The new government spent a long time agonizing about an acceptable use for this building. The palace now houses the Romanian Parliament and international conferences and can be visited.

Union Boulevard was initially intended as a communist-era Champs Elysees. It was never completed, but the sheer scale conveys something of the intent. Ironically, the demolition project reprived several historic churches from the Middle Ages (Prince Michael Monastery, Antim Monastery, and the Patriarchal Cathedral). These tiny Orthodox churches miraculously survived the rebuilding. They now stand hidden among the row of new buildings in the Civic Center. Wandering through these neighborhoods, you’ll frequently find churches in the courtyards of apartment buildings.

Other important places from this era are:

- Revolution Square: the place where the anti-communist revolution of 1989 began. Ceaușescu gave his final speech from the balcony of the former central committee of the Communist Party building when the crowds started booing him. While he briefly escaped by helicopter from the roof, the army opened fire against the crowds and many died.

- House of Free Press: in the North of the city, the vast white Stalinist building once housed the center of the state propaganda industry. The proximity of Herăstrau Park is another reason to come to this part of the city.

The transformation didn’t stop with the city center. As industrialization was a priority for the communist regime, factories were built around Bucharest. So there was a massive need for new blocks with apartments to house factory workers. Typical workers’ neighborhoods such as Militari, Berceni, and Dristor were quickly erected by the state, and the population doubled from one to two million in the 1960s and 70s.

The city was, therefore, ringed with apartment blocks expanding into the surrounding countryside. They included a park, state shops, libraries, and local farmers’ markets. While there’s not much to see on a walk here, you can at least imagine what life was like back then. Have a pretzel with soured milk from any pastry shop to experience the typical breakfast of a communist worker.

Bucharest Old Town

Bucharest today

During the communist regime, the ‘poor’ and the ‘rich’ replaced the middle class. After the 1989 revolution though, capitalism brought back conspicuous consumption and the “new” poor. The transition from a centralized, socialist, and old industrial economy to a liberal, free-markets and modern one was painful and riddled with corruption and inequalities.

This was quickly seen in Bucharest where previously banned glossy shops with Western designer clothes and luxury items quickly appeared, along with fine dining restaurants and hotels. Most of the population couldn’t afford them, but the change began.

From an architectural point of view, Bucharest after the 1989 revolution became a city of abandoned historical buildings from the Belle Epoque era, communist brutalist architecture and unfinished grandiose projects, and erratic development of modern constructions.

Starting in 2010, the city was significantly rejuvenated with many of its landmarks and public areas being restored. Skyscraper office buildings, shopping malls, and modern apartment buildings were built, thus shaking off the grim and old communist cloak.

The part of the old Bucharest center that survived communist demolitions is called the Old Town area (around Lipscani Street) received a long overdue revamp. It quickly becomes a hub for nightlife and culture, housing over 100 cafes, bars, restaurants, clubs, and shops for tourists. It’s a fascinating area that marks the city’s historic heart and resilience over centuries.

The aristocratic Victory Boulevard with its boyar houses and palaces was also restored. It’s still the main boulevard in the city and it features fashion shops, art boutiques, specialty coffee shops, restaurants, and hotels, thus making it an upmarket shopping street in Bucharest.

On weekends, the whole street becomes a lively pedestrian area. Families cycle from Victory Square to Dâmbovița River. Art workshops for kids and adults, urban outdoor theater plays, living statues, and cultural festivals happen almost every day in summer here.

Another notable example is the Univers Palace in the city center, next to Cișmigiu Garden. The old refurbished building houses spaces for meetings, events, parties, working, coffee shops, art galleries, theater, and courses. It proves how a quality restoration process can enhance the architectural value of a 19th-century building. Even though bullets badly scarred it during the ‘89 revolution, these signs were integrated into the new look of the building.

Suppose you want a panoramic view of the city’s newly established business district – then head to one of the skyscraper restaurants: Nor Sky Casual. Located in the northern part of the capital, you’ll get superb panoramic views of the city and blend in with the corporate middle class of the city. The restaurant is not too bad either with its international menu.

Conclusion

I hope you see how Bucharest is not just a historic city with typical landmarks to visit. It’s a place to discover slowly by going for a walk in its many areas to discover the landmarks and buildings representative of its rich history and societal transformations it went through.

The more you stay here, the better you’ll get to know and understand the city’s journey through time and its ability to reinvent itself.

- Buy Travel Insurance

- Get an eSim to be able to use your smartphone abroad.

- Get a Car Rental

- Get a universal plug adapter

- Book Your Accommodation HERE

- Search for Great Tours HERE

Travel to Bucharest, Romania – Episode 369

Travel to Bucharest, Romania – Episode 369 Malta Landmarks and the History Behind Them

Malta Landmarks and the History Behind Them What to do in Slovenia – Caves, Castles, Hikes, Horses and History

What to do in Slovenia – Caves, Castles, Hikes, Horses and History Road trip in Germany – Castles, Gardens, History and UNESCO sites in Eastern Germany

Road trip in Germany – Castles, Gardens, History and UNESCO sites in Eastern Germany