Hear about all of Canada’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites as the Amateur Traveler talks again to Gary Arndt of Everything-Everywhere.com about traveling to all 17 sites.

Some sites like Old Québec are easy to reach and others like Wood Buffalo and Nahanni National Parks (the last two that Gary visited) are quite remote.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites are sites determined by the United Nations to be worth preserving for all mankind. Some of these sites are cultural sites and some of them are natural sites. In Canada’s case, 8 are cultural sites and 9 are natural sites. The list of sites changes over time as new sites are added and occasionally sites are dropped from the list. Gary says “I always describe it as this is the hall of fame for national parks.”

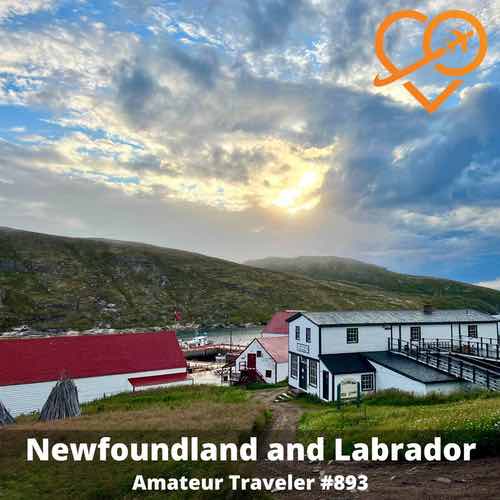

We start with the easternmost site, L’Anse aux Meadows, which is located at the very northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland. “L’Anse aux Meadows is the location where the Vikings created their first colony in North America. “What you see if you visit today is actually a reconstruction of the Viking village. But this is the location that had been written about and predated Columbus coming to the New World.” L’Anse aux Meadows was Canada’s first World Heritage Site. Gary tells us how cheese hurt the relations between the Norsemen and the natives.

“We can hop across the very narrow channel separating Newfoundland and Labrador. The most recent UNESCO site as of today is Red Bay which was a Basque whaling station that was established about 20 years after Columbus discovered America. They have found artifacts there dating back to, I want to say, 1520. There are rumors that the Basque fisherman may actually have been here before Columbus and they kept it a secret because they found the cod fishing to be so good.”

We work our way through historic Quebec, first nation sites like Head Smashed In Buffalo Jump and majestic sites like Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park and Canadian Rocky Mountain Park to some more sites in the remote north of Canada Nahanni and Wood Buffalo National Parks.

subscribe: rss feed | Apple podcasts

right click here to download (mp3)

right click here to download (iTunes version with pictures)

Show Notes

Everything Everywhere

Gary’s guide to UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Canada

Canada – UNESCO

L’Anse aux Meadows

Red Bay

Gros Morne National Park

Western Brook Pond

Old Town Lunenburg

Grand-Pré

Joggins Fossil Cliffs

Miguasha National Park

Old Québec

Rideau Canal

Pimachiowin Aki

Dinosaur Provincial Park

Royal Tyrrell Museum

Head Smashed In Buffalo Jump

Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park

Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks

Burgess Shale

Wood Buffalo National Park

Nahanni National Park

SGang Gwaay

1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

Kluane/Wrangell – St.Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek

Klondike

List of World Heritage Sites in Canada (Current and Proposed)

Transcript

Chris: Amateur Traveler Episode 437

Today, the Amateur Traveler talks about ancient cultural sites, amazing new vistas, and the wonders of Canada as we talk about all 17 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Canada.

Welcome to the Amateur Traveler. I’m your host, Chris Christensen. This episode of the Amateur Traveler could be sponsored by you. If you’re interested in sponsoring the Amateur Traveler and reaching people who are interested in traveling, contact me at host at amateurtraveler.com.

subscribe: rss feed | Apple podcasts

INTERVIEW

I’d like to welcome back to the show Gary Arndt, who has come to talk to us about Canadian UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Gary, welcome back to the show.

Gary: Thanks for having me for a ninth time.

Chris: Yeah, I was going to say that if you haven’t heard Gary’s voice on the show, then obviously you’re a new listener.

Gary will talk a little more about what Gary does at the end of the show, but Gary comes to us from Everything-Everywhere.com, and in your quest to see everything, you have been to every UNESCO World Heritage Site in Canada.

Gary: Yeah, I just got done with a 12,000-mile road trip and I visited my final two UNESCO sites; Wood Buffalo National Park and Nahanni National Park.

Chris: Now, you did not see all the sights on this particular road trip; you saw mostly the sites in the West on this road trip, as I recall.

Gary: Yeah. This has taken several years. We’re recording this in August 2014. I’ve been to all 17 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and there could be more if you’re listening to this at a later date.

Chris: Right; that’s a good point.

Well, let’s talk about the sites, and I’m thinking that it makes the most sense to do them geographically. Let’s start in the East and head to the West.

Gary: Okay. Probably the easternmost one, and actually one of the very first World Heritage Sites in the initial class in 1978, is L’Anse aux Meadows, which is located at the very northernmost tip of the island of Newfoundland.

L’Anse aux Meadows is actually the location that the Vikings initially created their very first colony in North America.

Chris: And we should say for those people who aren’t familiar with this, the UNESCO World Heritage Sites named by the UN as sites worth preserving for all mankind. Almost half, as it works out with Canada, are cultural and half are natural, and this is one of the cultural sites, obviously.

Gary: Yeah, I always describe it as this is like the hall of fame of National Parks.

Chris: I like that.

Gary: So these are like the best of the best. And L’Anse aux Meadows, what you see if you visit today is actually a reconstruction of the Viking village, because by the time they had found it – I think they found it in the early 1960s – they found some artifacts and some other things, but this is the location that had been written about and pre-dated Columbus actually coming to the New World.

Chris: Although it made less impact overall on the New World since those that stayed died out.

Gary: Well, they left eventually.

One of the funny stories that I learned about there is that they tried trading with the local natives, and it went well for a while and eventually they traded cheese with them, not realizing that the natives, never having eaten cheese before, were lactose intolerant, and they thought they were trying to be poisoned. That’s when things started to go sour, so to speak.

Chris: Oh, my. Did they try Poutine?

Gary: I don’t know, but I believe that the origins of Poutine may go back that far; the first cheese curds.

Chris: And so, there’s a re-creation there. It doesn’t seem like there’s a whole lot from the original – I mean, it’s a very significant site, but there’s not really a lot to see is my impression.

Gary: No. Like I said, you can see some dwellings that have been re-created; you can see some outlines in the ground of where dwellings used to be; there are a couple artifacts they found, including nails, some pins and some other metallic objects, and that’s really about it. It’s more the significance of what the site represents I think than what’s actually there.

Chris: And this one is – of the ones to get to, this is not one of the easiest ones to get to, but not the hardest to get to, as we’ll get to later on, right?

Gary: Yeah, I mean, I was able to drive there. It’s a long drive, but you just basically – I forget what the name of the highway is, but if you look at Newfoundland, there’s like a giant finger that juts north, and you’re basically just driving up to the tip of that finger.

Chris: Excellent. Where to next?

Gary: We can hop across the very narrow channel separating Newfoundland and Labrador. So that was the first UNESCO site from Canada. The most recent UNESCO site, as of today, is Red Bay, which was a Basque whaling station which was established about 20 years after Columbus discovered America. They have found artifacts there dating back to, I want to say, 1520, and you can still very clearly see where they had a fat rendering facility set up; there’s been several shipwrecks where they found artifacts; a lot of things from that region.

There are rumors – and I had read a book after I visited – that the Basque fishermen may have actually been here before Columbus and they kept it a secret because they found the cod fishing to be so good. They were drying cod – drying cod has to be done on land; you can’t do it on a ship, and they were coming back with dried cod, and they refused to tell anyone where their cod fishing ground was. So it’s believed that they may have even been here before that.

Chris: Interesting. I did not know there was any Basque exploration of the New World. This is news to me.

Gary: Oh, yeah, in fact, there’s still a lot of people with a Basque lineage that you’ll find in Newfoundland; Basque named villages and also surnames.

Chris: Interesting.

Gary: From there, we’ll go down the coast from L’Anse aux Meadows to Gros Morne National Park, which is a fantastic park. It’s primarily notable for I think it’s Mt. Gros Morne, which is the name of the mountain.

But what I found most interesting about it was it has one of the only freshwater fjords in the world.

Chris: I didn’t know you could have a freshwater fjord.

Gary: Well, it’s basically a fjord, and then it got landlocked. So, like sentiment or something kind of blocked it in, and then it eventually got filled with freshwater, and that’s kind of how it happened.

The name of the place where you can visit is called Western Brook Pond, and there are boat trips that go up into the fjord and you can see – it’s almost very similar to what you’ll see photos of in Norway. It’s much more green, but you have these very sheer cliffs on either side of it.

Chris: I see from the description on the website for UNESCO as high as 685 meters high, so pretty steep cliffs there. Interesting.

So this being obviously the first of the natural parks that we’re talking about then?

Gary: Yeah, and I think if you’re going to do a road trip, the three that we just discussed, Red Bay, L’Anse aux Meadows and Gros Morne, are all things that you could visit in one trip. The ferry from Newfoundland to Labrador is rather short; I think it’s like 13 miles between the two, and Red Bay is very close to where the ferry is, and L’Anse aux Meadows is also very close. And then driving from Gros Morne is I think maybe three hours, so maybe a bit more.

Chris: Excellent. Where to next?

Gary: I’ll probably go down to Nova Scotia in the old city of Lunenburg, which was a seafaring port and has a whole bunch of history, actually. It had a role in World War II, it had a role in fishing, it had a role in whaling; all sorts of different things. It’s a well-preserved town, and you really have the feel of being on an Atlantic fishing village.

Chris: When you say a role in World War II, I’m guessing this is not the well-known battle of Lunenburg that we’re talking about here, so what would the role be in World War II?

Gary: It was a training base I think for Norwegian sailors, and I think also some Canadians worked there as well. It wasn’t a major facility for it, but if nothing more, Lunenburg is just a very lovely place to visit. It’s one of the nicest little communities in Nova Scotia, and even if you didn’t care anything about World Heritage Sites, it’s probably still worth visiting.

Chris: Okay.

Gary: And then there are three of them in Nova Scotia that are very close. Lunenburg; the next is Grand Pre – which is also a relatively recent one – and Grand Pre commemorates the Acadian Diaspora. So, the Acadians were the initial French settlers in Nova Scotia – Nova Scotia used to be called Acadia – and the British basically kicked them out and they were sent all over the world, including Louisiana, and they are the ancestors of the Cajuns.

You can go there and you can see the initial Grand Pre. They have the farms that were initially settled; there’s a museum that’s there. Interestingly enough, as an American, there are photos of Louisiana Governor Huey Long taking a pilgrimage group to Grand Pre in the 1930s.

Chris: Interesting.

Gary: It’s very close to Halifax, as well. I think it’s less than an hour drive, and it’s all highway, so it’s a very easy site to get to if you’re going to be in Halifax.

And then the third one in Nova Scotia is the Joggins Fossil Cliffs, which is basically on the Bay of Fundy. There are several fossil-related sites around the world that are UNESCO sites; you have the paleontology sites, and the problem visiting them is that there’s not much to see because it’s been dug out of the ground already. So it’s entirely possible that you can walk along the shore – and there are some sea cliffs; they’re not huge – you can see fossils, but it’s really just kind of a good excuse to see the Bay of Fundy in action.

Chris: And the Bay of Fundy being the highest tides in the world?

Gary: Right. And there’s a place in New Brunswick, Hopewell Rocks, and that’s what most pictures of the Bay of Fundy focus on because there the tide is very vertical. You simply see it going up and down. But in Joggins, the tide is actually going out, so you can walk out like a kilometer at low tide. It just extends the shore very far into the Bay, and then it comes really far back. So it’s not that dramatic up and down so much as it’s just in and out.

Chris: And when one does walk out, does one need to be very careful about knowing what the tides schedule is; how quickly do the tides come in?

Gary: That’s probably a good idea. I wouldn’t personally go out that far, but yeah, I would definitely keep an eye on what the tides are.

So now, we’ll probably go into Quebec, and there’s another fossil site called Miguasha, which is a park in Quebec. One of the confusing things is the provincial parks in Quebec are called National Parks, but they are not part of Parks Canada. So this is technically a National Park in Quebec, but it’s not a National Park in Canada.

Chris: So this is one of those don’t tell the people in Quebec they’re not really a nation?

Gary: Right. And this, like Joggins, is a paleontology site, so it’s very hard to see a lot of things. It’s located on the St. Lawrence River, and probably not the most sexy of World Heritage Sites in Canada, but important for the fossils which are found there.

Chris: It sounds like that if we had to rank your sites, this is going to be in your bottom third.

Gary: Right, but if you’re doing a road trip from say Nova Scotia to Montreal or Toronto, you’re probably going to be driving very close to it, maybe like a half-hour off the highway. It’s just over the border from New Brunswick into Quebec, so if you wanted to stop, it would be pretty easy to do.

Chris: And we should say if you do find fossils, you’re not going to find big dinosaur fossils. This looks like it’s commemorating the Age of Fish, so you would find fish fossils.

Gary: Exactly. Many of the paleontology sites around the world – like, I remember going to the Sangiran site in Java where the Java man was found, which is an early human ancestor, and there’s just nothing there, because it’s not like you’re going to go digging around for bones or anything. These bones were found a long time ago, and same thing here.

The nice thing is that things like fish or even lower life forms, those fossils tend to be quite abundant compared to like dinosaurs or things like that.

Chris: Yeah, there are actually just smaller fossil sites just even up in the hills here in Santa Cruz, and we’ve gone fossil digging and you can find a shark tooth or something like that because there were a lot of them.

Gary: Yeah, and we’ll talk about another fossil site which is probably even more important and more special a bit later on in Western Canada.

Chris: Right.

Gary: But the next one is probably something a lot of people are familiar with, which is the old city of Quebec, which if you’ve been there, Quebec City is fantastic. I think it is probably the most European city in North America, maybe excluding Spanish colonial cities.

Chris: I was going to say St. Augustine is the other one that gets mentioned in terms of cities in the U.S. But certainly, in cities in Canada, this would be the one.

Gary: Yeah, and a fantastic feel, and I think that it should be on everyone’s list if you’re going to be making a trip to Canada.

Chris: I haven’t been there yet, so – this was the place that I was going to go to last year, and then unfortunately, a family funeral interrupted our trip there. So, yet to get to Quebec, and high on my list.

Gary: In the Old City, not a problem speaking English because it’s very tourist focused, but as you get into maybe some of the more rural areas of Quebec – not Montreal – sometimes, yeah, you don’t see people that speak English very much.

Chris: And just don’t mention they’re not a nation.

Gary: Yeah. And then the only one in Ontario, which may surprise people, is the Rideau Canal, which was initially designed so ships could bypass the United States, I think, where they could quickly get things. I think it was built after the War of 1812.

It goes through the spot where most people may visit; it would be in Ottawa, because it’s actually right next to the Parliament Building, which is actually one of the endpoints of the canal. And then I think it goes to Lake Erie at the southernmost point. Then it goes through several other cities as well. But right near the Parliament Building in Ottawa is probably the best place to see it. You can actually kind of see how the locks still operate. And on the canal, to this day, in the winter, there’s still I believe ice skating.

Chris: Right, one of the world’s longest ice skating rinks.

Gary: Right.

Chris: I’m just curious, as I’m looking at a picture of it as you’re talking about it, it looks like right by the Parliament Building there are a series of like eight or nine locks too, so it looks like eight locks to go up that very steep portion of the canal right there. So, very interesting if you like that sort of how things work kind of thing, that I do as an engineer. This is something that would be quite enjoyable.

Gary: And I was told that the initial point of the canal was to bypass – or something to do with getting around the United States because of the War of 1812, but then after that, it was never really used for that purpose. The first time it was actually used for that purpose I think was several years ago – it’s been in the last decade – where a guy took a sailboat up it to get around paying taxes or something in the U.S.

But yeah, the canal still functions.

Chris: Clearly, not as much in the wintertime.

Gary: No.

And from there, now we have to take a – we’re going to jump over – so this is in the far eastern part of Ontario, so we’re going to jump over all of Ontario, all of Manitoba, and all of Saskatchewan…

Chris: I was going to say, it doesn’t look like there’s anything in the middle there.

Gary: Not really. There’s a couple proposed sites, one in Manitoba, that would extend – parts of Manitoba, parts of Ontario, but that hasn’t been approved yet. I can’t even pronounce it; it’s like called Pimachiowin Aki or something like that.

Chris: So it’s a Native American site?

Gary: Right. I think it’s…

Chris: A First Nation site, sorry, if I’m in Canada.

Gary: Right. So the next one would probably be Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, which is another paleontology site. Dinosaur is a little bit more interesting than the other paleontology sites in Canada, just because the landscape in this area is very similar to the Badlands of South Dakota, if you’ve ever been there.

It’s very colorful; a lot of erosional features. I don’t think it’s a very popular attraction. It’s in the middle of the Prairies, it’s not next to the mountains, so the Prairies probably don’t get as much attention as the mountains do.

Chris: Well, and this is the one we talked about it when we talked about Alberta, saying that if you’re seeing this one, also stop in and see the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, where a lot of the fossils ended up.

Gary: Right. And in both Western Canada and the Western United States, that’s where they actually did find a lot of things like…

Chris: Albertosaurus and things, yeah.

Gray: The T. rex and stuff like that.

The next one is actually one of my – I thought it would be kind of lame before I went, but it has the best name of any World Heritage Site, it’s Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump.

What it is is a lot of people forget that prior to the arrival of the Europeans, natives in North America – in all of the Americas – didn’t have horses, and so when they hunted buffalo, one of the things they would do is basically, on foot, they would herd them and they would run them off a cliff. And then there would be women at the bottom of the cliff whose job was to butcher the buffalo, and they just sort of did it in an assembly-line format.

At Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, there is a natural kind of cliff in the landscape, kind of a hill that got cut in half, and it had been used for tens of thousands of years, and they found just layer after layer after layer of bones and other debris at the base of this cliff. They were even able to figure out that there was a period of like 1,000 years where they weren’t using it. So, for whatever reason, people stopped using it, and then came back 1,000 years later and started using it again.

But yeah, it’s a fascinating look at how they went about hunting and went about living in that part of the world prior to the arrival of Europeans.

Chris: Now, I don’t remember – it’s been a long time since I have been there – what they have to interpret the site there since this is basically just a cliff in terms of what there is to see.

Gary: There’s actually a quite good interpretive center.

Chris: That’s what I was thinking.

Gary: One of the things they do is they have a full-scale vertical replica of the cliff inside where they’ll have like a buffalo at the top, and then it kind of even goes below ground, where it shows you the different layers in different time periods going back in history of when people used it.

Chris: It’s interesting, because looking at the site, and I see that it was used for 6,000 years, and apparently, the buffalo just never got any the wiser to this trick.

Gary: Well, there was no one around to tell the other buffalo.

Chris: That’s true; good point.

Gary: So, we’re still in Alberta, and Alberta has the largest number of World Heritage Sites, so we’ll go to the third site Alberta, which is Waterton Lakes National Park, which is partnered – this is one of the two sites which are shared between the United States and Canada.

So, the technical name of the World Heritage Site is Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, so this is part Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta and part Glacier National Park in Montana.

Chris: And you say the two shared sites; is the other one Niagara, or what is the other one?

Gary: We will get to that in a bit, but the other one is shared between the Yukon, British Columbia, and Alaska. But no, Niagara is not a World Heritage Site.

Chris: Right, although one wonders why.

Gary: But basically, if you visit Glacier or Waterton, you’re visiting the World Heritage Site. I’ve been to both parks; I just visited Waterton for the first time. Waterton is significantly smaller than Glacier National Park, but it’s probably much more accessible and probably a little bit nicer. It’s not as much wilderness. Waterton Lake itself is very beautiful, and that’s what the park is pretty much around. There are boat trips you can take in the park and actually cross into the United States; one of the easiest border crossings in the United States basically because when you cross over on the lake, there’s absolutely nowhere to go because it’s ringed by mountains. There’s a guy there that says welcome to the United States. Want your passport stamped? It’s the absolute nicest you’re ever going to be treated by immigration officials coming into the U.S.

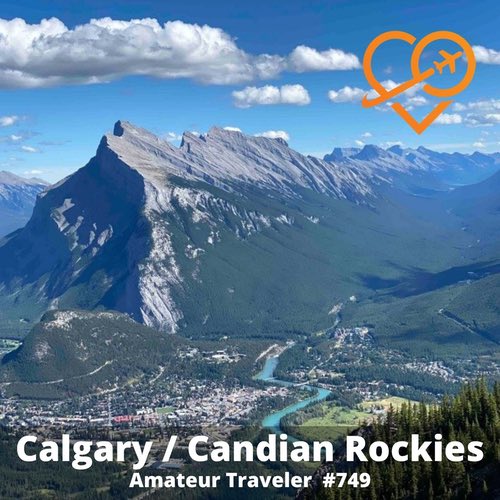

Going north then, probably the one most people are going to be familiar with is the Rocky Mountain National Parks of Canada, and this comprises several different parks. It’s Banff National Park, Jasper National Park, Kootenay National Park in British Columbia, Yoho National Park, and then there are two more Provincial parks in British Columbia which comprise the entire World Heritage Site.

Chris: I didn’t realize it was that large.

Gary: Yeah. And so, I was talking about another fossil site, this is where the Burgess Shale is found. So when Yoho – and the Burgess Shale, for people who don’t know what it is, this is where the Cambrian explosion was pretty much found. So this is where the first place the earliest multicellular life forms were discovered in the Burgess Shale, and it’s just – this point, all of a sudden, they find this multicellular life.

Now, it could very well be that there was multicellular life earlier, and there probably was, but it was all soft fleshy creatures that didn’t really make good fossils. The Burgess Shale is some of the most important fossil discoveries in the world, and Jasper and Banff National Parks are the two most popular and busy National Parks in all of Canada. I think Banff gets 3.5 million visitors a year; Jasper gets around 2-point-something million visitors a year, almost all of which come in July and August.

Chris: Right, and two of the prettiest parks in the world, in my opinion. I mean, they’re just fabulously beautiful.

Gary: Oh, absolutely beautiful. Moraine Lake in Banff is just absolutely stunning. I took some fantastic photos up and Jasper. Yeah, can’t go wrong. I think the Canadian Rockies are actually much more beautiful than the American Rockies, even though they’re not as tall.

Chris: I would agree.

Gary: They’re a bit more dramatic and the [indiscernible 23:42] are a bit nicer.

Chris: Unfortunately, the only time I’ve managed to take my family to the Canadian Rockies, there were terrible forest fires, so they haven’t gotten a chance, for instance, to go up in Sulfur Mountain in Banff and see the view because there was no view that day.

Gary: I was there this year again, and there were fires around Jasper. I was actually Jasper twice, and the first time I was there, I could barely even see the mountains from Jasper City.

So, from here, we’ll head north into Alberta to Wood Buffalo National Park.

Chris: And when you say north, you’re heading how – are you up in the way far north of Alberta?

Gary: We are at the northernmost border of Alberta. Wood Buffalo is two-thirds in Alberta, one-third in the Northwest Territory. This is the largest National Park in North America, and the second largest National Park in the world.

Chris: And we’ve now gone from millions of visitors a year, to what?

Gary: 3,000; half of which are locals, so about 1,500 people. To give you an idea, to drive to the entrance of Wood Buffalo in Fort Smith, Northwest Territory, which literally lies on the Alberta border, it’s about a day-and-a-half drive from Edmonton. And you literally almost have to hook around the park to get to the entrance.

Chris: And Edmonton already feels pretty darn far north.

Gary: Well, that’s the spooky thing about Canada. You go north, and you realize there’s a lot more north that’s north of here.

Chris: Right. The one country not particularly worried about global warming.

Gary: But Wood Buffalo is just enormous. I think it’s 45,000 square miles, and it is an enormous expanse of boreal forests and lakes and ponds and swamps and meadows. It is the nesting location of the whooping crane, which, oddly enough, it’s so difficult to get around in this region because everything is so wet that even the locals, the natives in this area, didn’t know that the whooping crane was nesting there. The whooping crane is extremely endangered. I think there’s only like 400 left the world.

If you get to Wood Buffalo, there’s a limited number of roads you can drive, not paved at all; gravel, and you’ll also see, as you might guess, Wood Buffalo, which are a slightly different species from the Prairie Buffalo. They’re a little bit bigger, but fundamentally the same.

The best way to see Wood Buffalo is by plane; to actually get up and fly around and see it for yourself. And even then, I was up in the air for four hours, and we still maybe only saw half the park.

Chris: And I would point out some of the beautiful photographs that Gary took of the park from there, but you said it was a very difficult park to access.

Gary: It is. I mean, it’s very far north, and in fact, I was working with Tourism Alberta; I was the very first journalist that has ever asked to go there. They had very little in the way of photos of the area, and the people I met who were visiting – it’s a very small number – but there were people that wanted to visit National Parks, and they were off to try to visit the National Parks of Canada and the United States, and they made the pilgrimage there.

I think it’s a great park, but it’s not an easy park. It’s not like Yosemite and Yellowstone, where you have these amazing rock formations. It’s a very subtle park. And just the sheer size of it; the only National Park in the world that’s bigger is the East Greenland National Park, which is basically one-third of the island of Greenland, and nobody lives there.

Chris: And it’s icepack, isn’t it?

Gary: Yeah. I mean, to give you an idea just how large this park is, it is a very substantial park, and it’s for the most part wilderness and it has never been developed and there’s never been much in the way of logging or any other activities there simply because it’s so difficult to get around.

It’s also home of the world’s largest beaver dam.

Chris: How large is the world’s largest beaver dam?

Gary: Larger than all others. I want to say it’s – I didn’t get to see it because it was pretty far south in the park, so we weren’t able to fly that far, but I think it’s – I want to say it’s like a couple hundred meters.

So, from here, we’ll go even further north to what I’ve been told is actually the very first World Heritage Site. So, along with L’Anse aux Meadows, it was one of the very first in the first initial group in 1978 that were created. I actually met a man during my most recent trip who worked for the UNESCO group with Canada who told me that at that initial meeting, this was the first one they voted on. So this could be considered the first World Heritage Site, and that is Nahanni National Park in the Northwest Territories.

Nahanni is I believe one of the greatest National Parks in the world. It’s up there with the Serengeti, Yosemite, the Great Barrier Reef, but nobody knows about it and nobody goes there. It gets about 800 visitors a year. You cannot drive there; there are no roads. The only way in is by floatplane, or I suppose you could hike, but that would be extremely difficult.

The centerpiece of the park is Virginia Falls, a waterfall which is taller than Niagara Falls, and has about as much volume as Victoria Falls in Africa.

There’s a website you can go to online that’s a listing of the world’s greatest waterfalls by all sorts of different measures, and the people that made this list have it as the number six waterfall in the world, and nobody knows about it.

Chris: I’ve certainly never heard about it.

Gary: It is an enormous park; slightly smaller than Wood Buffalo, and the mountains – and there are canyons, absolutely sheer faces on the cliffs, almost on par with the Grand Canyon. You’ll see mountains and granite exposures on a par with what you’ll see in Yosemite. It’s got a little bit of everything, but it’s just very, very difficult to access, and as such, it’s also very expensive.

So, first, you have to get to the Northwest Territory, which is not easy, and then you have to get a floatplane to get into the park. You basically have two options…

Chris: How much would a floatplane into the park cost?

Gary: Probably going to be in the neighborhood of $800 to $1,200.

So your options are a day trip, or, what a lot of people do is they raft down the Nahanni River, and depending on where you start, that will usually take you about a week.

Chris: I want to assume that’s not over the falls, so is that above or below the falls?

Gary: Both. So, the only portage you can make is at Virginia Falls. They have a facility there that Parks Canada runs; it’s really the only facility in the park. I think there were two people working there from Parks Canada, and they have a boardwalk where you can basically deflate your raft and take all your gear down the boardwalk to blow the falls.

The falls themselves are absolutely amazing, and the mountains and everything else around it are truly spectacular. I’ve sort of picked this as one of the places I kind of want to champion because nobody knows about it. And quite frankly, it’s never going to be a busy park. Even if they were to double the number of people visiting, that’s 1,600 people a year. It’s a fantastic place. I highly recommend people visiting it if they have a chance. And basically, you only have two months a year; you have July and August. That’s it. Maybe a little bit into September. And that’s the season.

Chris: Excellent.

Gary: So now, we’re going to British Columbia and another fantastic park, which is probably going to get changed soon. It’s not a park; it’s called S’Gang Gwaay. The spelling is S-‘-G with a line beneath it-A-N-G G-W-A-A-Y.

Chris: I thought that was a typo on the site when I saw that; the line underneath it, I thought that was a problem with their CSS on the website.

Gary: No, it’s a local Haida name, and I forget the meaning, but S’Gang Gwaay is basically the last place in the world where you can see original standing totem poles. It probably isn’t going to be there much longer. There were a series of villages – the Haida people in what used to be called the Queen Charlotte Islands, and now called Haida Gwaii, were one of the last North American people to meet Europeans. In the late 19th century, early 20th century, they had a massive die-off from smallpox and other diseases. About 90% of the people died. Most of the villages in the southern part of the islands were abandoned, and everyone went north to two communities, and S’Gang Gwaay was one of them.

As you go down, there are many different villages you can visit, and S’Gang Gwaay, they have basically made the decision to preserve it as much as they can, but the Haida people believe that totem poles have a life like people, so they have a beginning and an end. And so other than clearing away brush, if something takes root in one of the poles, they’ll pull it out. Other than that, that’s all they’re doing, and every year, they’re decaying a little more. I’ve had some of the guides tell me that it’s become very noticeable in the last several years. So if you still want to see this, you have maybe 10 years.

What’s going to happen I think is that – S’Gang Gwaay is within Gwaii Haanas National Park, and I think that they’re going to simply either expand it to include all of the park – which is a beautiful park, by the way, and one of the best National Parks in Canada – to include all of the cultural areas which are currently there, including S’Gang Gwaay as well as the natural things that it’s preserving as well.

Chris: Interesting. We should mention that when you said that they had 90% of the people died from smallpox, that was actually typical for the encounters with the Europeans and the Native Americans. The only difference is is that it happened later for them.

Gary: Yeah, there’s a great book I read called “1491,” which is the year before Columbus arrived, that goes through a lot of rethinking of what we know about the peoples of the Americas before Europeans arrived, and one of the things that they postulated was that the population was much larger than we thought and that the die-off was much larger than we thought, that the vast majority of the people in the New World died before they ever saw a European. In fact, the initial Europeans that came in the late 15th and early 16th centuries were the ones that brought the disease, and it basically, over a course of a century, swept through the Americas and – even before a lot of settlements came, the damage had already been done. And when we talk about, say, the greats herds of buffalo that existed in the Prairies, that was actually not normal. That was the result of a huge die-off of native populations because they weren’t hunting the buffalo, and that’s why you saw those huge herds.

But there’s also a lot of other things as well in terms of how they dealt with – used fire as a tool to manage hunting grounds and manage forests. Anyway, it’s a fascinating book.

Chris: Yeah, I’ve heard good things about it. I mean, the pilgrims, they ended up basically camping in the one uninhabited spot because an entire village had died off.

Gary: So there’s one more – and this is a mouthful – it’s Kluane/Wrangell- St. Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek World Heritage Site.

Chris: And this is the one that spans the border?

Gary: This is in British Columbia, Yukon, and Alaska. I was at the Kluane National Park part of it in the Yukon, but basically what it is, it’s an enormous ice field which covers these two Provinces and a big chunk of Alaska. And again, if you’re in Glacier Bay, I think you’re going to have a very different experience. I haven’t been to Glacier Bay yet, but it’s on my list. Most people do that by cruise ship, and you can see the glaciers capping off.

Visiting from Kluane was a very different experience. I did it – I’ve been there twice actually, and I’ve taken three aerial trips, one by helicopter, two by plane, and being able to view the glaciers from that level is absolutely fascinating. I actually found that doing it in the summer was better than the winter because you see glacial melt and you see these incredibly blue pools in the ice. I’ve never seen a color of blue like that anywhere else in nature but here. It’s just the deepest darkest blue you’ll ever see.

It is also the home of Mt. Logan, which is the highest point in Canada. So that is their equivalent to Mt. McKinley. It’s in Kluane National Park.

So those are the 17 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Canada. Just to briefly talk about some of the other ones that are proposed, the Klondike Gold Rush area around the Yukon in Canada up around Dawson City has been proposed; Quttinirpaaq, it is the northernmost tip of Nunavut in Canada in the northernmost bit of land in the Americas – that will be extremely difficult to visit if they ever pick that one; Mistaken Point, which is another fossil site; and there’s I think a couple other aboriginal sites in national parks, a couple in the north above the Arctic Circle, which I think would have a very good chance of being added as well because there are very few Arctic sites that are World Heritage Sites at this point.

Chris: Interesting. Now, you made a case for a couple of the parks particularly. Did any of them really surprise you?

Gary: Nahanni definitely did. S’Gang Gwaay, and if you include all of Gwaii Haanas National Park around that, is a fantastic park. The way you normally visit that is there are companies that do Zodiac trips, so you get on a Zodiac boat, and it’s about a four-day trip. You can visit the park, and no matter how hot it is, no matter what the temperature is, you’re going to freeze because when you’re going across the cold water, that wind is just very, very cold, so you actually have to dress for very cold weather, and then the moment the boat stops, you’re back in the warm weather again.

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump I thought was really great. Quebec City, like I said, is I think one of the finest colonial cities in North America. Red Bay I thought was very surprising. I didn’t know anything about the Acadian Diaspora before I went to Grand Pre, so that was very educational. I don’t think you can go wrong with most of these, especially if you find yourself in the region or nearby, they’re definitely worth taking a visit.

Chris: I don’t know that all of our usual questions apply as much, but let me ask a couple of them that I think do. You’re standing in the prettiest spot in all 17 of the parks, where you standing, and what are you looking at?

Gary: The prettiest would probably be Moraine Lake in Banff National Park or Maligne Lake in Jasper National Park.

Chris: Excellent. And again, you mentioned being up in Glacier Bay, the color of the water from the glaciers, I found some of that, at least in the one at Jasper, that you get some of that also run-off there that it’s an unusual blue.

Gary: You’ll see in a lot of the Rocky Mountain parks a grayish-blue, if it’s a running stream, and the color of the blue will often change on the time of day. So if you go in the middle of the day to like Moraine Lake, it’ll be a very deeper color of blue; in the very early mornings, not so much. And that primarily comes from what’s called rock flour, which is basically stuff that’s eroded off the mountains.

The type of blue you’ll see that’s sitting on a glacier, that comes from the ice, and that comes from the refraction of light through the ice. It’s not so much from solids suspended in the water so much because it’s literally just melted ice. But it has more to do with how the light is reflecting back from the ice, I think.

Chris: Excellent. I don’t know that it makes sense to try and get you to summarize 17 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in three words. Would you summarize your trip?

Gary: My ass hurts. Until you’ve driven up to the Northwest Territories – and the amazing thing is – so that is a really long drive. I drove all the way up from one end of Alberta to the other, and all the way down British Columbia from one end to the other. That’s a lot of driving. If you transpose that onto the United States, that’s a big chunk of it. And the amazing thing is once you get up to the Territories, there’s still most of Canada north of you. It’s just absolutely stunning.

And one of the funny things is when you get to the Northwest Territories, you are three to four hours between communities. There is truly and literally nothing between them, not even single homes, not nothing. So you have to – every time you come to any sort of city, you have to fill up your car with gas.

Chris: Interesting. The other thing I wanted to say is you were mentioning the Acadian Diaspora, and I did want to give a reference that actually if you want some of the background for that, that recently came up in the Revolutions podcast, which was talking about the series of events that led up to both the Revolutionary War in the U.S. is what they just covered, and now they’re covering the Revolutionary War in France and the War of the Spanish Succession, which we know as Queen Anne’s War or part of the French and Indian Wars is what led to that expulsion of the Acadians, and so it’s all tied into all the history that’s going on in Europe at that time. So that would be a good reference for you.

Gary, thanks so much for coming back on the show, and before we let you go, I’m going to tell you, those of you who haven’t heard Gary on the show before, you can also hear Gary talk about St. Helena; both the windward and the leeward islands of the Lesser Antilles; to the microstates of Europe, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, and San Marino; to the Canary Islands; to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in general – we did an overview episode, which is what kind of led to this – also to the Gulf States, Dubai, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait; and to Micronesia, all on other episodes of the Amateur Traveler.

Gary, where can people find more about your travels?

Gary: You can find me at Everything-Everywhere.com and pretty much every major social media platform.

Chris: And there you will find, since Gary isn’t telling you, the award-winning photography of Gary, and I think that you will particularly enjoy that if you go visit his site.

Gary, thanks so much for coming back on the Amateur Traveler.

Gary: Thanks for having me, and I’m looking forward to my 10th appearance on the show.

CLOSING

Chris: With that, we’re going to end this episode of the Amateur Traveler. I’m a little rushed today because I’m in Iceland and I’m off to see the Golden Circle tour with Nomadic Matt, who happens to be in town at the same time. So that should be great fun. If you have any questions, feel free to send an e-mail to host at amateurtraveler.com or leave a comment on this episode at AmateurTraveler.com. You’ll find the link to this episode as well as the links to all of the parks that we talked about in the lyrics for this episode. You can follow me on Twitter @Chris2x, and as always, thanks so much for listening.

Transcription sponsored by JayWay Travel, specialists in Central & Eastern Europe custom tours.

- Get a Car Rental

- Book Your Accommodation HERE

- Buy Travel Insurance

- Search for Great Tours HERE

+Chris Christensen | @chris2x | facebook

2 Responses to “Canada’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites – Episode 437”

Leave a Reply

Tags: audio travel podcast, featured, gary arndt, podcast, unesco

Banff & Calgary, Alberta, Canada – Episode 68

Banff & Calgary, Alberta, Canada – Episode 68 Travel to Southern Alberta – Episode 404

Travel to Southern Alberta – Episode 404 Travel to Calgary and the Canadian Rockies – Episode 749

Travel to Calgary and the Canadian Rockies – Episode 749 Travel to Newfoundland and Labrador – Episode 893

Travel to Newfoundland and Labrador – Episode 893

Tom Fuszard

Says:September 29th, 2014 at 2:47 pm

Chris:

I stumbled across your site while doing some searching. What an interesting concept: You embed audio files of interviews conducted while traveling. I find that very intriguing. As a marketing writer, I’ve interviewed countless individuals for various articles and other pieces. Never thought of including interviewing/reporting while on vacation. Some questions, if I may:

1. Do you usually set out on a trip intending to interview someone? Are people/experts generally wiling to sit down with you?

2. What brand and model of recorder and mic do you use? The audio quality is very good.

Keep up the good work.

– Tom Fuszard

New Berlin, Wis.

chris2x

Says:September 29th, 2014 at 3:26 pm

Tom,

1. My interviews are most often separate from my travel. While some shows (http://asia.amateurtraveler.com/travel-to-japan/ and http://europe.amateurtraveler.com/travel-flanders-belgium-travel-podcast/ for instance) are about my travels, most interviews are conducted from the comfort of my home office.

2. I use a Blue Yeti microphone ( for most interviews. When recording on the road as I did in the Flanders show above I used an iRig Mic Cast microphone connected to my cell phone. I do interviews over skype and record with CallRecorder.

Chris

links:

Blue Yeti – http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B002VA464S/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=B002VA464S&linkCode=as2&tag=chrischrissho-20&linkId=NFKXGPZHLPGQQ4NL

iRig Mic Cast – http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B00KY2ZNOC/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=B00KY2ZNOC&linkCode=as2&tag=chrischrissho-20&linkId=UAE3BJYJF7IJFDIU