Introduction

A unique National Historic Site is located in southern Colorado along the Arkansas River. Named Bent’s Old Fort, you might be confused. Who was Bent? If this is the old fort, where is the new fort? When you see it rising out of the prairie, you see why it is called a fort, then you find out it was never owned by any military. More confusion.

Today, you see a reconstruction of an essential part of US history. It is not a stretch to say that Bent’s Fort witnessed a massive expansion of the US and the beginning of the end for the Plains Tribe of Native Americans.

Before exploring the site, a little history is in order. Don’t worry; this is not high school history, and there is no test at the end.

Historical Context

Throughout the long history of Europeans’ contact with native people, few interactions have gone well for the natives. It is essential to note those who bucked the trend and treated the indigenous people as equals. The Bent brothers, Charles and William, were two such people. Along with a partner Ceran St.Vrain, they built a thriving business near where the plains and Rocky Mountains meet in Southwest Colorado. Their enterprise was centered on an adobe compound known then as Fort William, after one of the brothers. Today we call it Bent’s Old Fort and honor it with the designation of a National Historic Site.

Beginning in the 1830s, the lives of trappers started to change. European fashion no longer favored beaver felt hats. At the same time, the supply of furs dried up in the Missouri River area. Some returned to civilization, and some, like the Bents, moved south to the Arkansas River and buffalo hides trade. After pursuing the life of a mountain man and fur trapper from an early age, the brothers were well suited to the role of a trader to the natives.

By 1833, the Bents and Ceran St.Vrain formed a partnership. St.Vrain would mostly handle the business in Taos and Santa Fe. Charles would haul freight from St. Louis along the Santa Fe Trail, and William would manage their new compound located on the US side of the Mexican border.

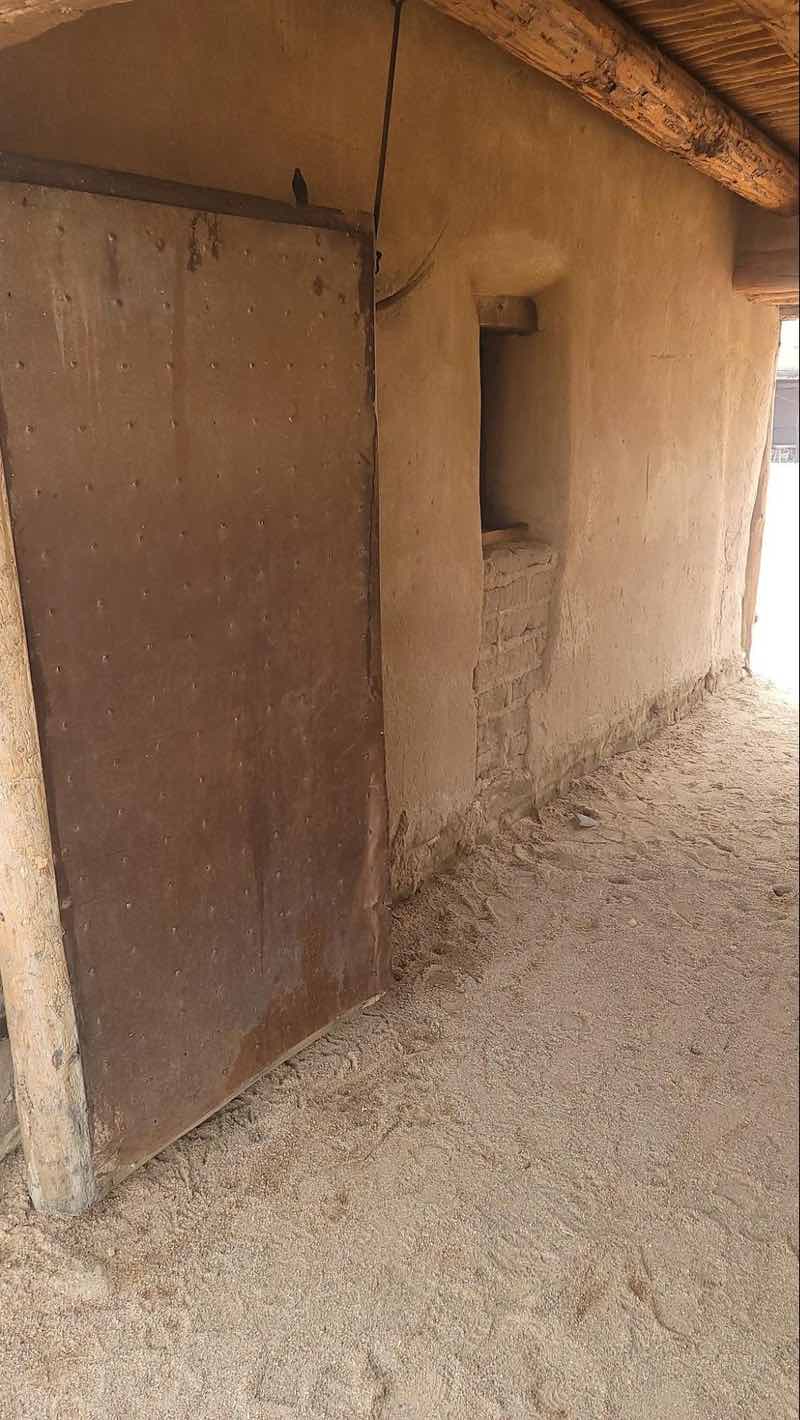

The compound was made in the Mexican style with adobe bricks. The thick walls soared up to fourteen feet high. There were round bastions on two corners armed with a small canon. A stout wooden gate closed off the main section. Corrals and livestock pens were located inside the thick walls. The two stories were filled with living quarters, work rooms, warehouse spaces, a kitchen, a dining hall, and, most importantly, the trading room. Little wonder the visitors and employees alike called it Fort William.

The Bents not only traded fairly with the surrounding tribes, but they also married indigenous women. And these were not like many of the trapper’s marriages, just someone to keep them warm at night until they returned to civilization. William married the daughter of a Cheyenne Chief named Owl Women around 1836. William became a sub-chief with the tribe in the 1840s because of his success in trading with them. The marriage lasted until 1847 when she died. He then lived with her sisters as secondary wives, typical of Cheyenne culture. They left him at some point, and he married a mixed-race woman shortly before he died in 1869.

Charles Bent married Maria Ignacia Jaramillo, born in Taos, then a Mexican city. He was not as involved with the native people as his brother. Charles was more of a politician, which cost him his life. After conquering Mexican territory north of the Rio Grande, General Steven Watts Kearny named him the territory’s governor. During the Taos Revolt of 1847, some citizens unhappy with the US takeover killed Charles, leaving his wife and children unharmed.

The third partner, Ceran St. Vrain, was from a noble family that fled France during the French Revolution, settling in Louisiana. He became a naturalized Mexican citizen in 1831. This allowed him to run businesses in Taos and Santa Fe. After the partnership dissolved, the most successful businessman of the three, he went on to found and run a business in the territory. The mill he ran is crumbling with huge cracks in its stone walls. But it still stands in Mora, New Mexico. Records do not show any official marriages, but he was known to have at least six children.

- Search for Great Tours HERE

- Book Your Accommodation HERE

- Log your park visits with a Passport To Your National Parks

- Get a Car Rental

- Buy Travel Insurance

During the peak of trading activity, with as few as little more than a dozen to well over a hundred people, the fort was a beehive of activity. Company employees came and went with furs, bison robes, and trade items for the tribes. Hunting parties left and returned with food for the kitchen. Independent traders visited to conduct business. Travelers on the Santa Fe Trail that ran past the fort would stop for a bit of civilization after weeks on the trail.

Those with the right connections might be invited to stay inside, while most just slept under their wagons. Meals were served in a large dining room, and guests could then retire to the billiards room, with a bar, on the second level. With a lack of women, the few who lived or worked at the fort were in high demand during the frequent dances.

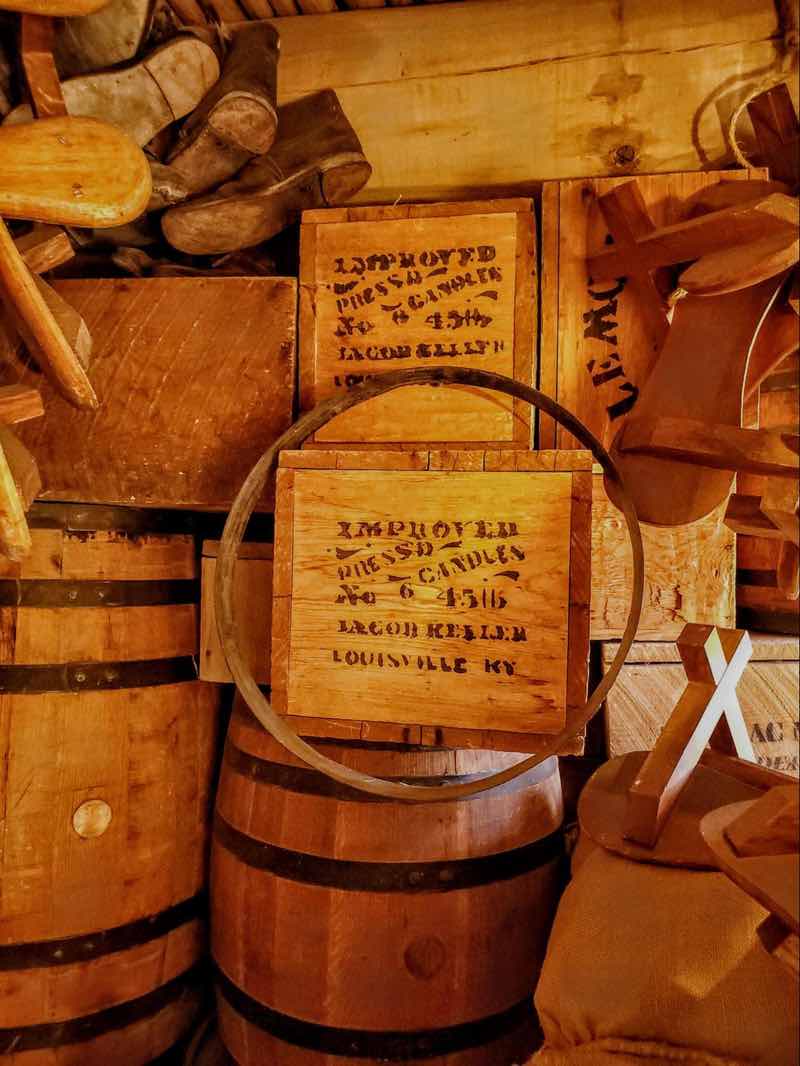

The center of activity was the trading room. There, furs and robes were exchanged for goods ranging from rifles, axes, and knives to trinkets and cloth. The trade added to the wealth the partners accumulated in their other ventures.

Looking like a fort and called a ‘fort,’ it was always a private enterprise, not part of any military. At least not officially. During the fifteen years Bent’s Fort was open, the world changed, sometimes violently. The peaceful nature of the fort and relations with the area tribes suddenly stopped in the summer of 1846 with the arrival of Brigadier General Steven Watts Kearny and the Army of the West on their way to invade Mexico.

The troops used the area around Bent’s Fort as a bivouac. The adobe building was a military hospital, supply depot, and commanding officer’s quarters. The soldiers and all their weapons frightened the tribes, and they stopped trading. After the troops left to invade Mexico, the store and hospital remained. The natives never returned in the same numbers as before. The firm was never paid for the use of its buildings or the loss of trade. William Bent became a broken man with his brother’s death and the partnership’s dissolution.

What happened next to Bent’s Fort is cloudy at best. What is known is that in August 1849, William loaded up several wagons with his trade goods and valuables from the fort and headed east. He built a fort in a new location several miles east of the original site, known as Bent’s New Fort, and the original became Bent’s Old Fort.

His trouble with the US Army did not end. He tried to sell the new building to them, then he tried leasing it. Ultimately, the Army decided it was built on land William did not own. Hence, the fort was illegal, and they took it and renamed it Fort Wise, later Fort Lyon.

Visiting Today

One of the best-restored sites along the Santa Fe Trail, Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site, is worth rerouting your trip to walk on the adobe walls, looking into rooms stuffed with trade goods, and talk to the costumed interpreters who wander the site.

Getting to Bent’s Old Fort

To get to Bent’s Old Fort NHS, you exit Interstate 25 at either Pueblo, Colorado (coming from the north, 80 miles) or Trinidad, Colorado (coming from the south, 90 miles.), driving on two-lane US Highways to La Junta, Colorado. Interstate 70 is about 100 miles north of La Junta and is a possible route to the site.

Please remember, this is the middle of the plains. You are not in a metropolitan area. Lodging and dining choices are limited. I recommend staying in La Junta. There are a handful of budget and mid-priced motels in town. There is also a scattering of restaurants. The site is located nine miles to the east. Alternatively, 50 miles west of the site is Lamar, Colorado. It also offers motels and a few restaurants. For campers, John Martin Reservoir State Park, with 200 camping sites, is 30 miles east of Bent’s Old Fort NHS.

Visiting the Fort

The site is open almost every day from 9:00 am until 4:00 pm. Shortly after parking your car, you are transported back to the 1840s. This is enhanced by placing the parking lot out of sight from the fort. Following a quarter-mile paved path, you pass a small cemetery on the left. It holds about a dozen burials from when the fort was in operation. None of the graves are marked. There is one marked grave for a Civil War soldier buried there.

Marshland stretches along the left side of the path. Watch for the Red-Winged Blackbirds perched on the plants. There is a walking trail that leads to the Arkansas River. For most of the life of the fort, the river was an international border between the US and Mexico, and the reason the fort was built here. The path gently curves towards the entrance of the fort.

Usually, there are one or two wagons on display. Interestingly, rangers or volunteers in period dress maintain them in period style. One of the bastions is clearly visible on the left corner of the fort. The cannon in the Bastion was mainly used for signaling and never shot to defend the fort. The entrance portal is protected by a gatehouse above the gate.

There are actually two stout iron-covered wooden gates. In the area between them is a small window on one wall, much like a modern ticket window. During normal operations, the outer gate would be open, allowing people to enter the passageway. However, the inner gate was closed, blocking the entrance into the fort itself. Visitors could trade through the small window.

The entrance station is to the left as you enter the fort proper. Visiting it continues your journey back in time. Rangers all dress as if they were in the 1840s. They may be a trapper or hunter employed by the partners or a Hispanic laborer. They remain primarily in character when you ask them questions. They will direct you to the Park Store, but ask them where the wood to build the fort came from, and they will talk about a sawmill in Taos and the Taos Lighting you could also get there.

Do not ignore the reenactors scattered throughout the fort. Ask them what their job is or how do they like the lonely fort. Talking to them is better than reading a book or website to learn about the history of this exciting site.

You are free to wander most parts of the fort. Tucked in the back, near the corrals, is an administrative office closed to the public. There is a wonderful gift shop and public restrooms adjacent to the offices. And do wander around. Look into the corners and rooms. I found a flock of chickens roosting in one room. Poke your head into a storeroom to see the boxes of trade goods or bundles of buffalo robes. There are an ever-present pair of peacocks strutting around the fort.

A highlight of my visits to historic sites is always the kitchen. I like to learn what and how people were fed in the past. At Bent’s Fort, there is the official kitchen where meals for the dining room were made. However, there are unofficial kitchens, little more than fire rings, where the laborers and others cooked their meals.

You are reminded just how primitive life on the 1840s plains was when you visit the doctor’s quarters. Bleeding was still a common method to “cure” patients. A few medications, including one based on mercury, were also prescribed. Or look into the two owners’ rooms. Not much more than a bed and a table with a few books.

The park receives just over 20,000 visitors a year. There is hardly ever a crowd visiting the park. You are often alone with your thoughts and the wind whispering echoes of the past. Check the park’s website for a calendar of special events.

In the past, there have been fur trappers’ rendezvous, visits from a team of oxen, and a reproduction wagon from the time of the Santa Fe Trail and Fourth of July celebration. During one special event, dozens of reenactors from around the West could give life to the old fort. These are all volunteers who create and equip a persona for the joy of others.

As a unit of the National Park Service, there is an entrance fee to visit. All of the multi-agency passes are honored. Every year the Park Service offers a few free days. Check the website for details. In addition to self-guided tours, there are Ranger lead programs most days. These are free.

The visitor’s center is located near the front gate. There are brochures and a Ranger to answer questions. There is also a short video about the fort. If you are interested in books or gifts, the Western National Park Association runs a bookstore at the back of the fort.

Additional Resources

An excellent book on the history of the fort and its reconstruction is “Bent’s Old Fort” from the State Historical Society. A different expert writes each chapter.

A book written by Lewis Garrard, “Wah-to-yah, and the Taos Trail: or Prairie travel and scalp dances, with a look at Los Rancheros from Muleback and the Rocky Mountain Campfire“, who visited and worked at the fort, gives many details found nowhere else. Wah-to-Yay is the native name for the Spanish Peaks, a prominent landmark in the area.

A diary was written by Susan Magoffin about her trip on The Santa Fe Trail along with the Army of the West on their way to invade Mexico. She talks about her time at the fort. She had a miscarriage while there. You can visit the room where she recovered.

Leave a Reply

Tags: article, colorado, national park

Minuteman Missile National Historic Site – A Flashback to the Cold War

Minuteman Missile National Historic Site – A Flashback to the Cold War Manzanar National Historic Site – Ghosts of WWII in the California Desert

Manzanar National Historic Site – Ghosts of WWII in the California Desert Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site – Lynn, Massachusetts – Video #92

Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site – Lynn, Massachusetts – Video #92 Rafting the Green River (Gates of Lodore) – Dinosaur National Monument – Colorado

Rafting the Green River (Gates of Lodore) – Dinosaur National Monument – Colorado