Valley Forge National Historical Park: The Turning Point in America’s Struggle For Independence

categories: USA TravelI have visited many American Revolutionary War sites in the Northeastern United States, but my favorite has always been Valley Forge in Pennsylvania. For me, Valley Forge has always felt like sacred ground. The historical park is not a monument to a major battle. There were no altercations fought there. Valley Forge was about survival and perseverance against overwhelming odds under the most difficult of circumstances.

General George Washington’s famous winter encampment was truly a turning point in the birth of the United States. The current national historic site remembers the sacrifice of the soldiers, camp followers, and other army personnel in overcoming adversity when it looked like the American cause had run out of options. I feel solemnity and respect for those who sacrificed every time I visit.

Valley Forge National Historical Park is located about 18 miles northwest of downtown Philadelphia. It is bordered by the Pennsylvania Turnpike on the south and is at the edge of the city of King of Prussia, a growing commercial and shopping area in suburban Philadelphia. The 3,500-acre historical park is an amazingly peaceful oasis amongst an area of expanding urban sprawl. It is a beautiful combination of rolling hills, forested areas, and open meadows. Looking across the scenic grass fields, it can be difficult to imagine the suffering and anguish that happened there.

Back in 1777, after losing many battles around Philadelphia, Washington’s Army needed a defensible location for winter quarters where they could keep watch on the British in the city of Philadelphia. At the same time, they had to be far enough away to be safe from attack. On December 19th, 1777, the soldiers and camp followers of Washington’s Army began the process of setting up a winter camp. Valley Forge seemed the perfect location because of the convergence of nearby rivers, roads, and abundant open farmland. It was also a place where soldiers could build huts for shelter, locate clean water, and procure food.

When I traveled to Valley Forge, I saw many green meadows and forests, but back in 1777, this was farmland. The presence of 12,000 soldiers would have turned the fields around Valley Forge into a muddy mess. Furthermore, many of the standing trees would have been cut down to build shelters and provide firewood for the troops. Washington and his officers secured lodging by renting nearby farmhouses and other permanent buildings.

Contrary to popular belief, the winter of 1777 was not overly cold and snowy. Valley Forge was not a battle against the elements but rather a survival against diseases such as smallpox, dysentery, and typhoid. It has been estimated that as many as 1,700 to 2,000 troops died during the winter encampment from disease and malnutrition.

Planning, determination, vaccinations, support from allies, and perseverance strengthened Washington’s Army through the winter encampment. His army survived and became a stronger, more cohesive force that proved it could match the British in battle. This was demonstrated when they broke camp in the spring of 1778 and faced the British in open-field fighting at the Battle of Monmouth, New Jersey. The British Army was forced to flee to the safety of New York City.

General Washington’s Headquarters at Valley Forge

Today’s national historical park came together over many years. Local citizens first made a determined effort to preserve Washington’s Valley Forge Headquarters starting in the late 1800s. The surrounding fields of Washington’s Winter Encampment became Pennsylvania’s first state park in 1893 under the direction of the Valley Forge Park Commission. In 1976, the state of Pennsylvania presented the park as a gift to the United States as part of the bicentennial celebration of the founding of the nation.

On July 4, 1976, Valley Forge officially became a National Historical Park. Over the years, many monuments and memorials were built to commemorate various events that took place in the area. Major historic buildings were preserved, museums were created, soldiers’ huts were reconstructed, and battlements were restored to show how the military encampment looked in 1777. Today the park even boasts recreational facilities for the many tourists that visit every year.

My recent visit was during autumn. At this time of year, the park becomes exceptionally beautiful as the foliage on the trees begins to change into a colorful backdrop of red, orange, and yellow. It is also a surprisingly tranquil time of the year to visit. I first stopped at the Visitor’s Center, where I received an extensive amount of information on how to best visit the park. A park volunteer informed me about driving options, renting a bicycle, an audio tour, and even a dial-in cell phone guide.

Seasonally, the park also offers a 90-minute bus/trolley tour for a fee. There is a small museum at the Visitor’s Center, along with an informative movie. When you visit, stay a few minutes after the movie to see two short films that give even more detailed information about the park and environment.

After the Visitor’s Center, the first thing I wanted to see was the famous soldier huts. It was estimated that as many as 1,300 to 1,500 huts were built during the original encampment. None of the original huts remain, but there are a small number of reconstructed huts scattered throughout the park. Nine huts of the Muhlenberg Brigade Encampment, often featured in promotional photographs, can be seen by walking a short distance from the Visitor’s Center.

On the first day I visited, I quickly ran into a few hundred children and adults who were attending a special Homeschooling event. The public was invited, and I saw some amazing presentations by re-enactors, historical organizations, park rangers, and environmental groups. Amazingly, when I returned the next day at the same time, I was the only person touring the huts.

For the remainder of the day, I followed the park’s most scenic drive, the 10-mile Encampment Tour Route.

Along the way, I visited the United States National Memorial Arch, statues, monuments, earthwork fortifications, artillery parks, a covered bridge, and historic buildings. Two locations that were highlights for me were Washington’s Headquarters and the Statue of Baron Von Steuben overlooking the Grand Parade Ground.

At Washington’s Headquarters, I could see the site where Washington and his officers met and discussed the fate of the American Army. I had an incredibly informative conversation with a park ranger stationed there who provided many insights into what took place and the people who were involved in making decisions. There are amazing personnel and resources in our national park system. All you have to do is ask questions and learn.

At the statue of Baron Von Steuben, I enjoyed one of the best viewing vistas the park has to offer.

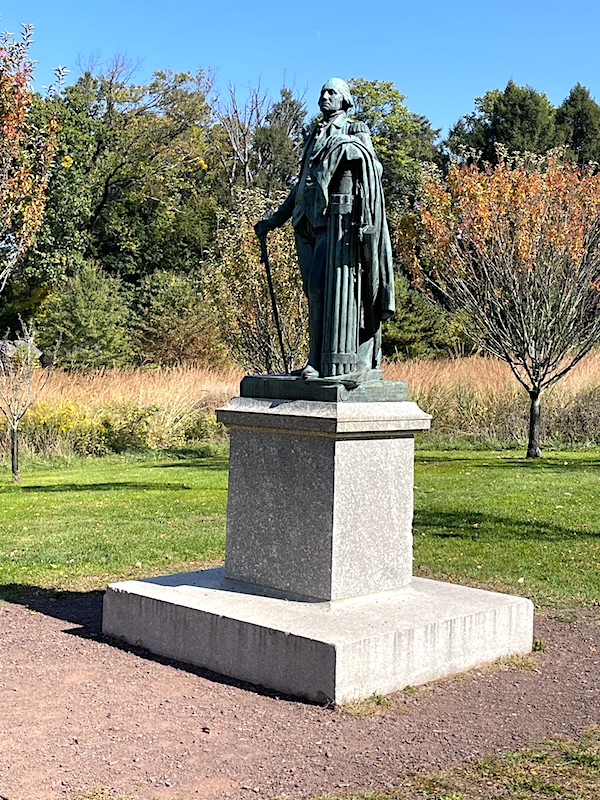

The bronze statue of General Anthony Wayne along the 10-mile Encampment Tour Route at Valley Forge

Near the von Steuben statue, the park also contains the Washington Memorial Chapel and the National Patriots Bell Tower carillon. Both structures were built as a tribute to George Washington by one of the founding members of the park. The Episcopal chapel is most noted for its stained-glass window depicting George Washington praying for his troops on the grounds of Valley Forge.

The Washington Memorial Chapel and the National Patriots Bell Tower carillon

Other historic structures found within the park are the headquarters of the Continental generals, the Marquis de Lafayette, Henry Knox, Jedediah (or Jedidiah) Huntington, James Mitchell Varnum, and William Alexander Lord Stirling.

An artillery park with the United States National Memorial Arch in the background

Valley Forge can be visited at any time of the year. During the winter, you can get a sense of the wind, cold, and bleak conditions experienced by Washington’s Army. Spring is pleasant, and weekdays often see an abundance of school groups. Summers are the busiest, but also provide more touring options, such as trolley tours and bicycle renting.

Autumn often features pleasant weather, changing leaves, and fewer crowds. Weekends are most popular at Valley Forge since the park is popular with locals who like to run, jog, hike, bike, and enjoy nature in the park. You can visit most of the major sites in a few hours, but I suggest taking your time to walk and enjoy the park. I spent two afternoons visiting sites and taking photographs.

a redoubt protecting the Muhlenberg Brigade Encampment

Within a 25-mile radius, there are many other significant sites associated with the American Revolutionary War, such as Philadelphia‘s Independence National Historical Park, Brandywine Battlefield, and Germantown’s Cliveden House. Less than an hour away, state parks in both Pennsylvania and New Jersey are dedicated to the site of Washington’s famous crossing of the Delaware River and the Battle of Trenton. A short drive of 60 to 90 minutes can also take you to historic buildings, battlefields, and winter encampment sites in New Jersey.

A monument honoring the soldiers of New Jersey within Valley Forge National Historical Park

All of these are worthwhile places to investigate and relive the history of American Independence in the Eastern United States. In my experience, though, none of them quite encapsulates the sacrifice, bravery, determination, and perseverance that allowed the American cause to survive and be reborn, as do the rolling meadows of Valley Forge.

Leave a Reply

Tags: article, national park, pennsylvania

Red Oak Victory Ship – Home Front National Historical Park, California

Red Oak Victory Ship – Home Front National Historical Park, California Death Valley National Park – Amateur Traveler Video #77

Death Valley National Park – Amateur Traveler Video #77 A Summer Journey to Death Valley National Park

A Summer Journey to Death Valley National Park 36 Hours at Yosemite: A First Time Visit To America’s Famous National Park

36 Hours at Yosemite: A First Time Visit To America’s Famous National Park