Warm Nights In A Mongolian Winter

categories: asia travelAlthough more than 1 million people live in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, everything feels sparse.

The area seems too large for the city’s buildings and its residents, the power cuts out so frequently that the outages go unacknowledged, and all the food comes drenched in ketchup (including the ubiquitous noodles).

Black Market

On the second day of my brief stay, some other travelers and I visited the city’s Black Market. To say it was chaotic would be an understatement: People climbed over garage doors to get in for free and, the moment I entered, I was almost knocked over by two women carrying mattresses on their heads.

Inside, there were “sellers” of all kinds: TV remotes, fireplaces, carpets, sacks, hats and, best of all, those who sold whatever they had managed to lay their hands on — a sheep’s knees, a flaking dominoes set, three football pin badges, a pair of miniature Buddha statues, a sword and a wooden riding saddle.

Turning into an alley, I met a man hacking the head off a goat with an axe. Stepping over the blood, I moved into the hardware section, where I negotiated a path through the chainsaw demonstrations and into the food court. Here, there were lumps of butter the size of my head; the cheeses were even larger. Before I had a chance to buy anything, I collided with women pushing palates of bloody meat. They were followed by children pushing the organs, thus completing the grim procession.

Lost in Ulaanbaatar

After a few hours of drifting through the mayhem, we chose to walk back to the hostel. We crossed the main road using the underpass, and then decided to take a “shortcut.” We turned off of the main road past a series of disheveled playgrounds; there were no swings attached to the huge metal hooks, so the frames resembled horrifying torture devices.

Twenty minutes later, we were lost.

With mounting concern, we walked through a rough housing estate. Above our heads, groceries hung from the windows to keep them frozen. Meanwhile, at ground zero, there was only rubble and dust.

“Do you think we should turn back?” asked a woman in our group, her hand gripping her wallet through her jeans.

“No, I think we should press on,” replied another.

Now I knew we were in trouble. We had begun to talk as if we were at war.

We followed a bridge across a patch of water, which was filled with trash. On the other side, we could just about make out mountain peaks through the haze of smog emanating from nearby factories.

“Look!” exclaimed one member of our group, pointing to the hills like a character from Lord of The Rings. “We’re going the right way!”

“How did you work that out?” the man at her side fired back.

“Because the hills are over there!”

“Yes,” he groaned. “But how does that help? We haven’t seen them before, so we don’t know where they are.”

He was right, of course, so we silently dropped back into line.

The only good thing about getting lost is the euphoria you feel when you find your way. On this occasion, we did so by luck rather than judgment: To our surprise, a random alley led onto the main road. Even then, one group member pulled a map from his pocket, to ensure we weren’t taking any more chances.

That evening, we stood on the hostel balcony and gazed out at the cityscape. It was a bewildering mix of old apartment lots, factory smoke, fenced yurts, building sites and white hills — all boxed in by a thick wall of smog. We all had had enough of the city and were happy to be spending the following few days in the countryside.

Gorkhi-Terelj National Park

The next morning, we hired a minivan to take us there. Before long, the city was just a haze behind us and we entered the dusty land of limbo, which separated the city from the countryside.

A few hours later, hills emerged in the distance. The mid-morning sun reflected the sky to give their white peaks a blueish tint. With the brake pressed to the floor, our driver negotiated a slushy slope toward a small camp of yurts.

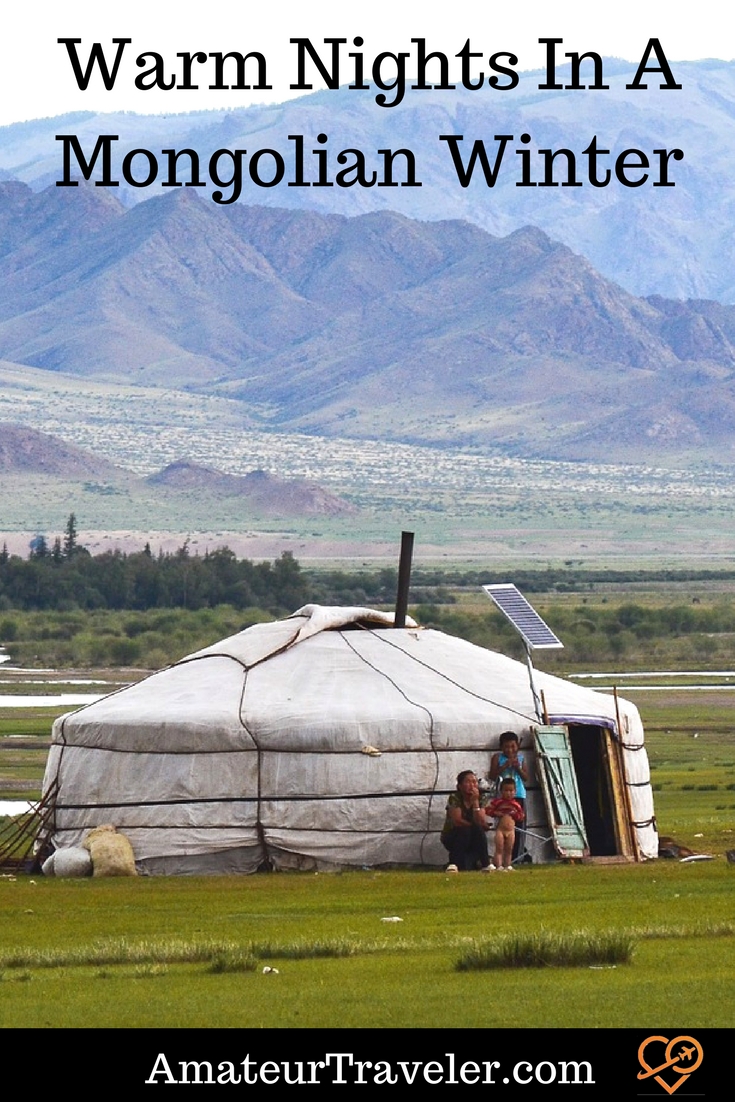

Gorkhi-Terelj National Park is only about 80 kilometers northeast of Ulaanbaatar, but it felt as if it was another country. The soaring mountains made everything seem minuscule; including our hosts who came out of their yurts to greet us with big grins.

- Buy Travel Insurance

- Get a Car Rental

- Search for Great Tours HERE

- Get a universal plug adapter

- Get an eSim to be able to use your smartphone abroad.

- Book Your Accommodation HERE

A Night in a Yurt

Mongolians have been living in yurts since the 6th century, and it is thought that as many as 40 percent of the population still live in them today. We were to spend the next few nights in one, so were happy to discover they were much larger inside than they looked. There was room for six wooden beds, which were neatly arranged around a large black stove.

That evening, I discovered the stove got extremely hot. Unable to sleep, I threw off my blanket and clutched the steel bedposts in an effort to cool my body. Then the door swung open and my body relaxed with the breeze. A figure entered carrying an armful of coal and firewood; he added this to the stove, making the heat even more intolerable.

The next morning, a fellow traveller named Jim — one half of the British honeymooning couple who had opted against a beach holiday — asked me if I had felt hot the night before.

“Very,” I replied.

He shook his head.

“I don’t want to sound ungrateful, but if that man comes in again tomorrow night, I’m telling him not to add any more firewood. Honestly, I could hardly take it.”

The rest of us nodded our flushed faces in agreement.

Mongolian Horses

Later that morning, we were scheduled to ride some Mongolian horses.

Our excitement faded somewhat when we discovered the horses were out of breath and overweight. We climbed onto them all the same and, 30 minutes later, our camp disappeared from view as we moved into a land of white isolation — the only sign of civilization was the odd, solitary yurt.

I had envisaged cantering through the countryside, but instead our horses refused to do anything but walk slowly. We tried everything to make them trot: First shouting “choo!” as our guide suggested, and then whispering into their ears. Finally, we yelled at them in English (which was not suggested by our guide).

By the time we arrived back at the camp, the sun was descending. Cattle wandered into their evening pens, dogs yapped as the cows clomped toward them, and a toddler hit the dogs with a stick before being lifted off her feet by her laughing mother. Everything was happening in slow motion; the plodding animals, the people working, even the birds in the sky seemed to fly at a slower pace.

Warm Nights in Winter

That evening, we drank a few beers in our yurt, then shut the door, and turned in for the night.

Twenty minutes later, it was boiling hot.

The door opened and a pile of wood hit the floor.

An English voice travelled through the darkness: “We’re very grateful, but please don’t put any more wood on the stove. We don’t need it.”

Ignoring this, the man opened the stove.

The English voice became more frantic, “Honestly! We don’t need it.”

In response, the man dropped the wood into the stove and shut the door behind him.

Coughing through the heat, I headed outside.

Moments later, I was joined by the others, who also had decided that standing in their underwear in the snow was preferable to lying inside in the furnace.

“I tried to stop him!” Jim said.

“We heard you,” another replied.

“I don’t want to be ungrateful,” Jim repeated. “But the heat is too much. I mean, it’s so hot in there the candle has melted — and it wasn’t even lit.”

Feeling giddy, I dropped to my haunches and pressed my hands into the snow. One of the girls wiped the sweat from her face with the back of her arm. Framed by the backdrop of snowy mountains, she looked almost comical. However, this was one of the reasons I enjoyed traveling so much: You could never predict what might happen. Here we were, in the Mongolian countryside in the middle of winter when the temperature was -20 degrees, and inexplicably, we were all too hot.

Leave a Reply

Tags: article, mongolia, ulaanbaatar

Travel to Mongolia – Episode 603

Travel to Mongolia – Episode 603 Our Travels – Sherry Ott Traveled to Mongolia

Our Travels – Sherry Ott Traveled to Mongolia Travel to Mongolia – Episode 111

Travel to Mongolia – Episode 111 Finding the English Instructions on a Chinese Pay Phone

Finding the English Instructions on a Chinese Pay Phone