3 Days with the Dalai Lama

categories: asia travelIt’s a mystery to me

We have a greed

With which we have agreed

When you think you have to want more than you need

Until you have it all you won’t be freed

Spiti Valley is a remote, almost isolated region in the north-east of the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, about 100 km from the Tibetan border. The valley is quiet, road traffic is minimal and villagers live off the land and do not have much need to venture beyond their homes. The capital village (not city or town, but village) is sleepy Kaza. But for three days, Kaza was buzzing as His Holiness the Dalai Lama flew in for a visit.

Police officer keeping the peace

The day he arrived, the main road of Kaza was lined on one side with thousands of people, mostly Spitian and Tibetan families and Buddhist monks and nuns. Chai vendors who always seem to find a way to sell their chai everywhere in India were also present, setting up temporary chai stalls just across from the gompa (monastery).

Security was very high and Indian police with their AK-47s were everywhere, amongst the crowds and perched on top of roofs nearby. One major downside to all this security was that no cameras were allowed into the gompa while HH Dalai Lama was there so I didn’t get any pictures of him.

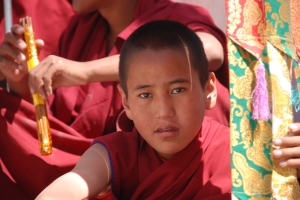

Burning incense

I pressed my luck and brought my big SLR with me up to the front gate figuring I could talk my way into bringing it in. No luck. I ended up having to go all the way back to my guest house to drop it off and then returning.

He came to Kaza inaugurate the new gompa, to share some knowledge about emptiness and impermanence and to initiate those who wished to be into the way of Avalokitshevara, the Buddha of Compassion. The most recognized Buddhist mantra, “Om Mane Padme Om”, is a mantra from this Buddha that brings compassion to those who say the mantra.

Buddhist nuns awaiting His Holiness’s arrival

Being initiated into this mantra allows the chanter of the mantra to gain the benefits of it. Which makes me wonder what happened to all those times I’ve said that mantra before this initiation.

Spitian culture and language is similar to Tibetan culture and language and the primary religion in the valley is Tibetan Buddhism. Not surprisingly, it seemed that every Spitian from the valley came to Kaza for these talks. Add to that a couple of hundred Westerners and you’ve got a village where all the hotels are fully booked and power outages are happening every night as the power grid in Kaza wasn’t designed to handle so many people.

Family waiting alongside the road

HH Dalai Lama had a few hundred tents set up au gratis (as opposed to au gratin) near the river for those who couldn’t find accommodation or couldn’t afford it. I had heard that he really takes care of practicalities for those coming to see him talk and it really did seem like it.

As we sat and listened to him talk, monks would be walking by serving butter tea and bread. If you’ve never had butter tea before then consider yourself lucky.

Welcome HHDL!

It is more like a salty broth than tea. It is an oily white concoction that looks somewhat appetizing till you take a sip and wish you could Ctrl-Z that last action. Luckily my friend Tamsin loved the stuff so I’d keep giving her mine as I continued trying it each day thinking that it would somehow be better.

I met up with Tamsin in my shared jeep ride from Manali to Kaza, along with Marni and Lindsay, two sisters from the States, and Penpa, a 28 year old Tibetan guy who somehow is always smiling and laughing, and this after I’ve been traveling with him for a couple of weeks now.

Buddhist monk

We all clicked really well as the group is quite positive and easy going and our self-dubbed “family” ended up sharing one big room during our stay in Kaza.

Each morning around 7 a.m. a couple of us would head out early to the gompa (monastery) to try and save a few places for the group. Locals and Tibetans had the prime location right in front HH Dalai Lama while the foreigners were off to the side, with a good view of his left side. So many locals turned out that they began moving into the foreigners section and soon outnumbered all of us.

The main gompa

The talks were all in Tibetan but thanks to this advanced technology called the “radio” and a live translator sitting among us, we were able to tune our radios into 97.9 FM and catch the live translation.

While we were waiting for the talks to begin, a monk was chanting “Om Mane Padme Om” rapidly and repeatedly over the speaker system. I thought there was a 50-50 chance he would achieve enlightenment that morning with the pace at which he was chanting.

His helicopter makes a loop overhead

Around 9 a.m. HH Dalai Lama would arrive and we all stood as he made his way to the front of his throne, bent down to rest on his knees and did his three prostrations to the throne. Once he was seated then the ritual was for people to do three prostrations to him before taking our seats. For someone in his 70’s, he is still a pretty fit man. He managed to do the prostrations and climbed into his throne on his own strength. And he spoke with a strong and at times animated voice.

But the best part about seeing HH Dalai Lama speak, even not understanding Tibetan, is just hearing his infectious laugh. It comes unannounced and can come at any time.

Monks and nuns line the street

During the initiation ceremony, as he was saying his prayers and chanting a mantra, in every way a serious ceremony, there was a pause, and then you just hear this “heh heh heh”. And that is just the start. He continues a few more times. “Heh heh heh,” and you can’t help but laugh too. He’s got a childlike, but not childish, way about him. When he was not talking, such as when the Hindi translator was repeating what was just said to the audience, HH Dalai Lama would be gently rocking back and forth or side to side in his throne, looking out at the crowd.

Buddhist monk in traditional headdress

Sometimes he would reach into his robe, pull out a tissue and wipe his glasses, dry his eyes or blow his nose. Then when the Hindi translator was through and it was time to speak again, he would in an almost casual way just lean towards the microphone and say “Oh yeah. Okay.”

When all the pre-talking rites and rituals were completed, we sat down, opened up our notebooks and tuned our radios in to 97.9 FM. “Relax, enjoy the bread and enjoy the tea. And listen to me also. Heh heh heh.” And with that we began the teachings.

“What is I?”

“Does I have a beginning or not?”

“Does I have an end or not?”

Those were the questions he began with. He compared the answers to these questions as they would be answered from the perspectives of the different major religions in the world. At no point did HH Dalai Lama every claim that one religion was more correct than another, but instead encouraged people to follow the religions of our parents but with knowledge and harmony of other religions.

“What is I?” You can also ask “What is this computer?” The point of the exercise is to try and identify the one thing, one piece, that you can say “Aha, that is I, or that is the computer.” You’ll find you can’t.

Things come into existence through mere designation. Analyze any object and you’ll find that you can’t find it. Here is an example. Let’s say you’re taking a walk on a mountain. You pick up a beautiful rock, then you throw it into the river below.

Wake me up when he gets here

Is this still a mountain? What if you throw 100 more rocks of the mountain? What if a billion rocks are thrown off the mountain till there is just a handful left? At what point does it stop being a mountain? When people stop calling it a mountain.

This is the foundation of emptiness, one of the final teachings of Buddhism. The notion of emptiness in Buddhism basically means that nothing in this world exists on its own, that nothing exists independently of anything else. We designate things as ‘a mountain’, ‘a car’, or ‘I’ because we have this notion of duality, that there is an independent I and each object we see is also independent. But this is a completely false view.

Take the computer you’re using right now as an example. It is made up of many parts, each of which was built and assembled by a machine or a person.

Monks and nuns lining up with their kattas

Before that, an engineer designed how this computer should be built, and he probably used a white board to draw up his ideas. (Note, I am making a strong assumption that the engineers who designed your computer were males. I should know given the ratio of males/females in my computer engineering classes in college). The white board itself was probably made in a factory and includes chemicals that were created in a lab by a scientist who drove his Ford Escort to work. The Ford Escort was assembled by people and machines in Dayton, Ohio. Etc. Etc. So all of those things played a role in you having this computer in front of you.

By the way I’m probably not doing justice to how HH Dalai Lama explained this and even as I’m reading through mine and Lindsay’s notes I’m having trouble explaining it, so apologies if this doesn’t make too much sense.

Buddhist monk

It is difficult stuff to comprehend! But that’s what I like about Buddhism. It is very analytical, based on analyzing and understanding your own experiences, your thoughts, behaviors and emotions. In many ways it is more science than religion.

The other thing he spent a lot of time talking about was attachment and impermanence, that nothing in this world is eternal and yet we cling to everything as though they will last forever. We cling to our material possessions, our relationships and even more importantly, to our lives, as though we expect them to be here for all time. Another exercise he had us try was to find anything in this world that is impermanent, something that will never change.

Two young monks sharing some Fanta

I was tempted to mention the fact that the Detroit Lions total of zero Super Bowl championships was a number that would probably never change in a million lifetimes. But other than that, you’ll find it impossible.

Everything changes. That George Foreman grill you got for Christmas two years ago probably looks a lot different now than it did when you unwrapped it. And twenty years from now it’ll probably be in some scrap heap in New Jersey. Your new car is no longer new soon after you leave the lot. Nothing doesn’t change.

And from all of this we are to extrapolate that yes, even we, with these super duper bodies of ours are impermanent. Even with our Kirkland Signature daily-multi-vitamin supplements and Cod Liver fish oil tablets and our three-times-a-week gym routine, we’re still going to fade away.

Warming up the band

So if this is all true, then why do we have such strong attachments to things, to people, to our own lives even? It is a futile exercise. On the flip side, I think there is a danger here when one begins thinking that if nothing lasts then that means that nothing matters. That is completely opposite to the point HH Dalai Lama is trying to make it. We should appreciate what we have in each moment when we have it but when it is gone, we should let it go and not get caught up trying to bring it back.

This is a really hard thing to do for many reasons. We live in a world where we are measured by the mountains of material possessions we have. We become so attached to these things and to the perception they help us project of ourselves to others that we fight tooth and nail to keep the things we have. If someone scratches your car door, steals your camera, spills your beer, blood pressure rises accordingly.

On a side note, there is something about long term traveling that makes you stop caring so much about your material possessions. I think it has to do with the fact that all of your belongings are in your backpack and so you end up having way less things than you would at home. And you begin to realize that you don’t really need so much to get by or be happy in this world (just an iPhone and some Indian curry is good enough for me). When you begin accumulating too many things, you can physically feel the burden of the extra weight on your back. At home you simply shove them into your storage closet that has become a veritable Jenga-game-in-waiting and forget about it.

There were three days of talks and I’ve only tried to capture the general idea of what he spoke about. It isn’t the hardest stuff in the world to understand but it is difficult to absorb and just writing it out here has been a good challenge in recalling everything we heard.

We did have one very curious happening. The day before the Avalokitshevara initiation we were given strands of kusha grass to place under our pillow and mattress at night. It was intended to keep away bad dreams and perhaps also give us pleasant dreams. The intention is to basically protect us during the couple of days of the initiation. The next morning as we were walking to the gompa, I asked Lindsay and Marni if they had any dreams. Marni, like me, hadn’t had any dreams that she could remember but Lindsay had a dream where she had visited many different Buddhist temples.

HH Dalai Lama began his talks that morning talking about the kusha grass and the interpretation of the dreams. The first thing he said was “If you had any dreams about visiting temples, then that is a good dream.” We were floored. This was exactly Lindsay’s dream. But before we could get too excited about it, he reminded all of us that “good or bad dreams, remember that they are gone now so don’t put too much importance on them.”

In other words, don’t get attached.

Tokyo Itinerary – 3 Days (with 4 Day and 5 Day options)

Tokyo Itinerary – 3 Days (with 4 Day and 5 Day options) Things To Do in Manila Philippines – History, Shopping, Sunsets and Day Trips

Things To Do in Manila Philippines – History, Shopping, Sunsets and Day Trips 10 Amazing Places To Visit In India

10 Amazing Places To Visit In India Things to do in Lhasa, Tibet – Visiting the Roof of the World

Things to do in Lhasa, Tibet – Visiting the Roof of the World